Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months more than a year to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 63rd installment.

This isn’t the final installment of “The Great Alan Moore Reread,” with a post on the Alan Moore legacy and another one on my All-Time Alan Moore Top Ten still to come, but it’s the last chance to look at an Alan Moore comic book series and write about what I find upon rereading. Even if I respond to new Alan Moore projects when they come out—that Nemo book from Top Shelf is scheduled for the winter of 2013 and who knows what other Moore comics might trickle out over the next decade?—they will be first-reads, first-responses and it’s certainly likely, if not definite, that the best of Alan Moore’s comic book work is well behind him.

So this is basically it, then. The final comic book series I’ll be writing about for this more-than-a-year-Tor.com project of mine, which has taken me from Marvelman through Swamp Thing and Watchmen and into From Hell and Violator and Tom Strong and beyond. I didn’t write about every single comic Moore worked on. I skipped that short he did with Peter Bagge. And his spoken-word-pieces-turned-to-graphic-narrative with Eddie Campbell. And I mostly ignored his earliest work as a cartoonist, and his prose projects, like a B. J. and the Bear story, or his novel Voice of the Fire.

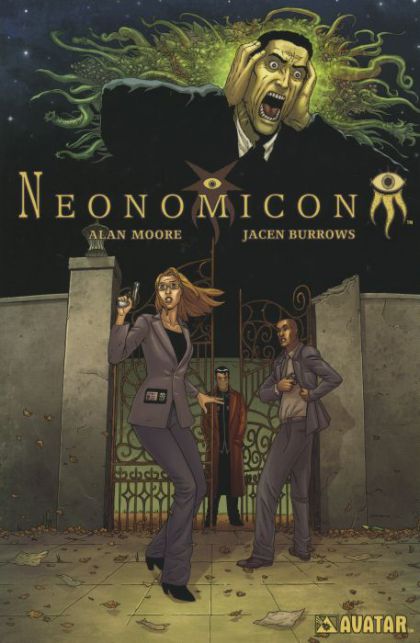

Here we are, in the end, with Neonomicon. Alan Moore’s last significant comic book work, other than the follow-up chapters of the larger League of Extraordinary Gentlemen saga.

And Neonomicon began, sort of, all the way back in 1994. With a book subtitled “A Tribute to H. P. Lovecraft.”

In “The Courtyard,” Alan Moore’s contribution to The Starry Wisdom, a 1994 anthology in which notable writers from J. G. Ballard to Ramsey Campbell (and even Grant Morrison) write stories in the mold of Lovecraft, we meet a racist, unhinged narrator who happens to be an FBI agent. According to his unreliable narration, his investigation into a series of murders in Red Hook has led him to infiltrate a cult-like nightclub where he gets hooked into Aklo, a potent white powder that gives the narrator visions of Lovecraftian nightmares.

Moore’s story is not just a tribute to Lovecraft’s work, it’s a kind of post-mortem weaving together of some of Lovecraft’s disparate tales. Moore ties the kidnappings described in “Horror at Red Hook” into the Cthulhu monstrosities of his more famous stories.

And by the end of “The Courtyard,” the narrator—whose name turns out to be Aldo Sax, which I don’t think is mentioned in the story itself—has revealed himself to be one of the murderers himself, ritually carving the bodies of his victims in the manner of the killers he’s been pursuing. Or maybe it’s been him all along, committing these murders. His madness is palpable, and the truth is obscured.

Neonomicon #1-4 (Avatar Press, July 2010-Feb. 2011)

Moore would follow up on the events of 1994’s prose tale with this four-issue comic book series from Avatar Press, published sixteen years after the Starry Wisdom original, and 84 years after H. P. Lovecraft’s “Horror in Red Hook.” Moore may have been motivated to follow up on some lingering ideas he, and/or Lovecraft, had explored all those years ago, but in his own words, he was motivated by something a bit more urgent: he needed some money.

As Moore describes in a 2010 interview with Wired.com, when asked about his then-upcoming Neonomicon, “Funnily enough, that is one of the most unpleasant things I have ever written. It was just at the time when I finally parted company with DC Comics over something dreadful that happened around the Watchmen film. Kevin [O’Neill] and I found that we were having some hiccups in our payments, after storming out of DC. I had a tax bill coming up, and I needed some money quickly. So I happened to be talking to William [Christensen] from Avatar, and he suggested that he could provide some if I was up for doing a four-part series, so I did.”

Pragmatic, indeed. And while we’re all delving into these kinds of comic books and providing context for and analysis of their artistic merit, it’s sometimes refreshing to hear a creator, even before the release of a project, admit that he did it for the cash. It’s a job.

But that doesn’t mean that Neonomicon automatically lacks artistic merit, and in that Wired interview, Moore goes on to explain more about what led him to write this particular story, when he could have written a four-issue story about a rock talking to a bunny about jazz and still received a paycheck from Avatar Press just for their ability to slap his name on the cover of a comic and get retailers to take notice. But he didn’t. He wrote Neonomicon, a particularly brutal, nasty, unpleasant comic. “Although I took it to pay off the tax bill,” says Moore, “I’m always going to make sure I try and make it the best possible story I can. With Neonomicon, because I was in a very misanthropic state due to all the problems we had been having, I probably wasn’t at my most cheery. So Neonomicon is very black, and I’m only using ‘black’ to describe it because there isn’t a darker color.”

Neonomicon certainly lacks the underlying wit, or even irony, of so many of Alan Moore’s other horror comics. It’s relentless, like From Hell, but without the structural complexity or the unrestrained ambition to tell a story on such a large narrative canvas. It’s grotesque, like the nastier moments of early Swamp Thing or the infamous fifteenth issue of Miracleman, but without the distancing effect of genre deconstruction. Neonomicon is more like a snuff film, or whatever it is that Alex was forced to watch during the deployment of the Ludovico Technique, with eyes peeled open, in A Clockwork Orange. We can’t look away, no matter how horrible.

Well, we can, and many probably did by stopping their reading of Neonomicon after its second issue and dismissing it as a comic in which Alan Moore uses the horrors of rape in lieu of an actual story. But that dismissal doesn’t address the comic book series as a whole, and though a monstrous rape sequence is at its core, there’s a narrative reason for it, and a contextual reason:

Moore was simultaneously exploring the birth of a terrible beast and embracing the sickening legacy of Lovecraft’s foul perspective.

As Moore explains in the quite-illuminating Wired interview, “It’s got all of the things that tend to be glossed over in Lovecraft: the racism, the suppressed sex. Lovecraft will refer to nameless rites that are obviously sexual, but he will never give them name. I put all that stuff back in. There is sexuality in this, quite violent sexuality which is very unpleasant.”

Moore continues: “After a while of writing and reading it, I thought, ‘Hmmm, that was much too nasty; I shouldn’t have done that. I should have probably waited until I was in a better mood.’ But when I saw what [artist] Jacen Burrows had done with it, I thought, ‘Actually, this is pretty good!’ [Laughs] I wanted to go back and read through my scripts. And yes, it is every bit as unpleasant as I remember, but it’s quite good. I think it’s an unusual take on Lovecraft that might upset some aficionados. Or it might upset some perfectly ordinary human beings!”

I’m sure it did.

What Moore does with Neonomicon is to bring in two FBI agents to follow up on the events described—irrationally—in Moore’s “The Courtyard.” Agent Lamper is black and Agent Brears is a woman with a sex addiction. They are caricatures ready for exploitation by the regular-guy-and-gal cultists they encounter in Red Hook. Lamper dies quickly, and Brears is tortured. She’s set up as the sexual prey of one of the aquatic, Lovecraftian monstrosities who lives in the sewers below the town. The rape sequences are explicitly detailed. It is vile, page after page.

Aldo Sax appears in the story, in the Hannibal Lecter role of the imprisoned crazy man, though Lamper later says, “He’s scary, but not how I thought he was gonna be…I thought he was gonna be like Hannibal Lecter, you know? Scary as in, ‘what’s he gonna do?’ Instead, it’s more like ‘what the fuck happened to him?’” This is no Hollywood movie version of an FBI investigation. The telling is off. It’s as if the spirit of Lovecraft has imbued this story with a horrific anxiety from which there’s no escape. It’s an unfolding towards increasing despair, rather than a story arc with rising action and conflict and climax and resolution. Agent Brears is forced into passivity. She is victimized. And though there is a beginning, middle, and end to her suffering, she is not at all in control of it.

But she is not really the protagonist of the story, it turns out. At least, not in the cosmic sense. She is merely the vessel for something greater and more terrible. A rough beast slouches toward Red Hook to be born. Brears is the opposite of Virgin Mary. The Annunciation is not at all divine. Cthulhu waits to emerge.

That’s where Alan Moore leaves us in the end, exposed to the raw horrors beneath the surface of the world, with a cosmic monster floating in its multi-dimensional amniotic fluid. Alan Moore says he was in a misanthropic mood when he wrote Neonomicon and it shows. There’s no hope for any of us by the story’s final pages.

Is this a bleak, unbearable way to end the “reread” portion of “The Great Alan Moore Reread”? Probably. But it’s all we have. Until next time!

NEXT TIME: A reflection on the Alan Moore legacy. And, in two weeks, I conclude the Great Alan Moore Reread with my All-Time Alan Moore Top Ten list.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

Neonomicon is difficult to defend, as it definitely feels like a compromise between Moore’s work and Avatar’s typical grindhouse exploitation. I don’t think it’s worthless, though. He doesn’t exactly rise above the horror tropes of characters who were just made to be abused, but he does subvert them in unexpected ways. Issue #2 would have been the end of a normal plot, and instead that’s the real launching point for the story.

The reason I (sort of) liked it was for what he did with the Lovecraft mythos. Much like Gaiman’s Beowulf or Twain’s Connecticut Yankee, he seemed to be saying “Ok, say these are stories about real events, but they’re still STORIES about the events. What would the reality have been?” He didn’t have the best answer, but I have a soft spot for stories like that.

(Tangentially related: I would recommend The Courtyard. I only read the comic version, and it sounds like Moore didn’t directly write that? I don’t remember clearly, but Avatar has a history of adapting Moore’s prose stories. Your description doesn’t really do the story justice, though I can’t say more without spoilers. It’s a pure “Alan Moore being Alan Moore” ending, though.)

I agree that this is a hard book to read–I knew I was in for a hard ride when the credits page assured me that everyone pictured here was over 18.

But then Moore had somewhat prepared me for this with his previous (I think) works, Lost Girls and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (especially the Black Dossier). Part of the fun to this revision of previous works is the Nevins-ish spotting of the referent: Red Hook is from Lovecraft, the Club Zothique is named after something Clark Ashton Smith made, Aklo is from Arthur Machen. (In a way, Lovecraft himself is a proto-Moore in his love of referencing older material.)

And like those other works, Neonomicon forces us to read what’s repressed in those stories or ignored in modern homages, which is here, Lovecraft’s racism and his aversion to sex/frequent reference to perverse interminglings. In that way, I feel this story’s main audience is Lovecraft fans rather than Moore fans. (In the same way that, say, Alice Randall’s Wind Done Gone was aimed at, if not read by, fans of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind.)

(Minor note: I thought the second story took place largely in Salem, MA, not Red Hook. Am I wrong?)

But the only part where I disagree with you is when you say that this book is bleak. I mean, Lovecraft is bleak: the universe is uncaring and alien to human desires and needs. That’s pretty bleak (unless you’re Lawrence Krauss). But the end of this book offers something strangely joyful in the birth of the elder gods. I mean, this human world isn’t doing so great, so maybe it’s time to try something else. Something with more tentacles.

(See also Cabin in the Woods.)

There was an analysis of the art in the first issue on Youtube. There were metatextual goings-on. It’s rather fascinating I highly recommend THAT analysis.

As to Tim’s comparison to Moore’s “From Hell”, “From Hell” is a much longer work focusing on a discredited investigation of the White Chapel murders. Alan Moore, in an interview, years ago, was working on a big Lovecraft project but he lost all of his writings and research materials in a taxi-cab. The materials were never recovered. I suspect if Moore hadn’t lost those materials we would have had a much longer work on HP Lovecraft of which “Neonomicon” is only the slightest of glimpses into what could have been. It probably would have been Moore’s greatest work.

Timbo, I’ve loved your entire Alan Moore Reread saga! There aren’t a lot of blogs I follow religiously, but I’ve read every single word of every one of your posts in this series. Excellent stuff.

I’ve got one favor to ask, though: Please consider doing one extra post where you go through the rest of Alan Moore’s writing (at least the comics related stuff, although I wouldn’t mind seeing your comments on his prose work too). Within the context of your Reread series, a look at the comics that have been adopted from Alan Moore’s prose/poetry/spoken-word work would be of great interest. And even more importantly, I think, would be a final round-up of any other comics Moore actually wrote or co-wrote himself – like the short you mention at the top of this post, and the American Flagg backup story + one-shot that another commenter has mentioned a few times before (I’m quite curious about that, as I’d never heard about it before).

You certainly don’t need to devote a full post to each of these things – I think one post could wrap it all up. Even just a sentence or two on each project in his bibliography that you haven’t touched upon yet, or an overview essay that skims through all of it at once. Like your earlier Reread articles where you zipped through his early-career backup stories.

It’d be a nice cap to the series, and could give your readers some ideas about what lesser Alan Moore works might be worth tracking down.

Cheers mate!

I had been thinking of the ending of Neonomicon as Agent Brears reclaiming her agency–writing a new future for the world out of the horror to which she was subjected. The Deep One shows her genuine concern, even tenderness, when he realizes that she is their madonna, and from that point forward, from among the tightly constrained choices offered her, Brears chooses to move forward.

As I was noodling that thought, though, I realized that it’s the same empowerment that Janni gets in League 1910: calling on something vaster and more deadly, for revenge. There’s the possibility that the New Old Ones that Brears will birth will be something wonderful, but, really, all that matters to her is that the old world, the world that did that to her, be wiped away.

David Drake, in his early days as a writer of supernatural horror, wrote “Than Curse the Darkness”, about the types of people who become Nyarthathotep’s cultists. The short answer: they are the people for whom this world has proven to be such a horror that they will take any chance of delivery, no matter how abominable.

I loved “Neonomicon,” personally. It’s a horrifying tale, but hey; it’s a HORROR comic! I think it’s a good, necessary thing for horror to actually horrify every once in a while.

It’s probably not one of Moore’s best works, by any means. On the other hand, most of his lesser works are still semi-masterpieces.

I’d not known this series was going on prior to reading the Moore’s-top-ten post, so now I get the pleasure of going back and reading through the entire series of posts. Looks like it’s going to be a lot of fun! Thanks in advance!